|

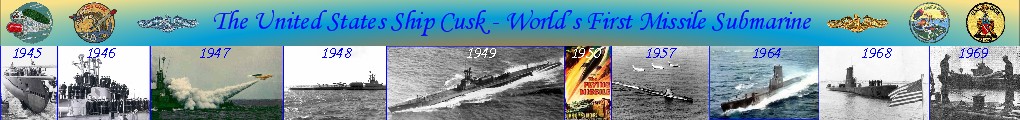

| |

Sea Stories

Memories from Cusk crewmembers and

other interesting submarine stories

What's the difference

between a fairy tale and a Sea Story?

Well, a fairy tale begins

with, "Once upon a time...", and a Sea Story begins with, "This is no sh*%..."

|

Bunk Bags

Reminiscing about those memorable, good for anything

green nylon bags that hung from just about every "rack" on the boat.

Author unknown. Submitted by Rick "Ptomaine" Greer,

USS Cusk, 1965 - 1967 |

Operational Readiness Inspection

(ORI)

A humorous story from a young Cusk sailor about how the

#1 "heavie" thrower didn't exactly have a good day.

Story by Norm Carkeek, USS Cusk, 1949 - 1951 |

The Sub that Sank a Train

A true story about how crewmembers from the USS

Barb sabotaged a Japanese train during World War II in the only ground

combat operation

on the Japanese 'homeland' of World War II.

The Saboteurs, under the command of Commander

Eugene Fluckey included Paul G. "Swish" Saunders, who later served as

COB of the Cusk in 1950.

Author unknown. Story submitted by Jerry Weaver,

USS Cusk, 1967 - 1969 |

|

The Puppy

Sam Lyons tells how to handle a puppy when nature calls

at sea.

Story by Sam Lyons,

USS Cusk, 1953 - 1959 |

Air Power

Norm Carkeek's funny story about how the Cusk went down,

or thought she did and ended up fanning the air.

Story by Norm Carkeek,

USS Cusk, 1949 - 1951 |

The

Paint Job

Reminiscing about those memorable, good for anything

green nylon bags that hung from just about every "rack" on the boat.

Story by Mike Van Hoy,

USS Cusk, 1959 - 1960 |

|

Hot, not exactly

straight, not exactly normal

On patrol in North Vietnamese waters, a torpedo, minus

its warhead is launched at an Australian destroyer turns and comes back at us.

Story by Tom Roseland, USS Cusk, 1966 - 1969 |

Operation Iceberg

Four great stories about the Cusk's early years.

Stories by Don Boberick, USS Cusk, 1946 |

A Last Look

The decommissioning of a warship is a sad thing to see,

especially if it has been your home for years.

Author Tom Roseland,

USS Cusk, 1966 - 1969 |

|

|

What Grandpa did

during the Cold War

Some great stories, reminiscing, and Cusk history by a

former Cusk crewmember

Story by Billy Hrbacek, USS Cusk, 1959 - 1963 |

|

In the beginning...

|

In the beginning was the word, and the

word was God and all else was darkness and void and without form. So God

created the heavens and the earth. He created the sun and the moon and the

stars, so that their light might pierce the darkness. And the earth, God

divided between the land and the sea, and these He filled with many assorted

creatures.

And from the

slime, in a land called Lympstone, God made dark, salty creatures

that inhabited the seashore. He called them Marines, He

dressed them accordingly, in bright colors so that their betters may

more easily find them in the holes and burrows that they'd scoured

out of the ground.

And God said,

"Whilst at their appointed labors they will devour worms, maggots, C

and K rations and all creatures that creep or crawl". The

flighty creatures of the air, He called Airdales, and these He

clothed in uniforms which were ruffled, perfumed, and pretty.

He gave them great floating cities with flat roofs in which to live,

where they gathered and formed huge multitudes. They carried

out heathen rites and ceremonies by day and by night upon the roof

amidst thunderous noise. They were given God's blue sky and

their existence was on the backs of others.

And the

surface creatures of the sea, God called Skimmers, who supported the

Airdales and with a twinkle in His eye and a sense of humor only He

could have, He gave them all gedunks, polluted with much stickywater,

to drink. God gave them big grey "targets" to go to sea in.

He gave them many splendid uniforms to wear. And He gave them

all the world's exotic and wonderful places to visit. He gave

them pen and paper so that they could write home every week, and He

gave them ropeyarn Sunday at sea and a laundry so they could clean

and polish their splendid uniforms. (When you are God it is

very easy to get carried away with your own great and wondrous

benevolence) .

And on the

seventh day, as you know, God rested from his labors. And on

the eighth day at 0755, just before Colors, God looked down upon the

earth and He was not a happy man. God knew He had not quite

achieved perfection, so He thought about his labors, and in His

infinite wisdom, He created a divine creature, His masterpiece, and

this He called a Submariner. A child of heaven.

And these

Submariners, whom God created in His own image, and to whom He gave

his most cherished gift, great intelligence, were to be of the deep,

and to them He gave more of his greatest gifts. He gave them

black steel messengers of death called the "Smoke Boat" class in

which to roam the depths of his oceans, and He gave them His arrows

and slingshots, the Mark 14 torpedo of burnished brass and black,

and the Mark 37 of green, to wage war against the forces of Satan

and all evil.

He heaped

great knowledge and understanding upon them, in order that they may

more easily win their greatest challenge, to pass their

Qualification Test and be skilled in the great works God had charged

them with.

The finest of

these men, God called "Diesel Boat Submariners" for they made all

happen beyond the understanding of other men. He gave His

Submariners hotels in which to live when they were exhausted and

weary from doing God’s will. He gave them fortitude to consume

vast quantities of beer and booze, to sustain them in their arduous

tasks, performed in His name.

He gave them

great food, submarine pay and occasionally, subsistence so that they

might entertain the Ladies of the "Starlight", "White Hat", and the

"Horse and Cow" on Saturday nights and impress the heck out of the

creatures He called "Skimmers” and "Jar Heads".

And at the

end of the eighth day, God again looked down upon the earth and saw

all was good in His realm. But God was not happy because, in

the course of His mighty labors He had forgotten one thing. He

had not kept a pair of "Dolphins" for Himself.

But He

thought about it and considered it and finally He consoled himself,

in the certain knowledge that - - -

"Not Just Anybody Can Be a

Submariner!"

- author unknown |

Bunk Bags:

If you never rode the boats, this is going to sound silly and

make absolutely no damn sense to you. If you did, you will remember the

damn things and probably smile.

The contraptions were simply called bunk bags. Not 'U.S. Navy

Bags, Bunk, Type II Mod 6, Unit of Issue, One Each'. Not 'Shipboard Personal

Gear Storage Pouch (Submarine) with Zipper'... Just goddamn 'bunk bags'.

They were elongated bags, designed specifically for horizontal passageway

storage, hung from the tubular bunk frames on diesel boats. They were

ugly, a sickening shade of lime-green (which incidentally, closely resembled the

color of barf after a three-day drunk) and had four snap straps that connected

them to the bunk rail.

It is my understanding that they were intended to eliminate the

noise level created by Gillette safety razors, Zippo lighters, busted Timex

watches, dice, flashlights, coins, and shrunken heads, purchased as gifts for

wives, from rattling around in an aluminum side locker and giving away your

position. They were either that lime-green or some kind of gray tweed and

they were uglier than a blind man's bride. But they had many desirable

qualities if you were a nomadic resident of a submersible septic tank.

First, they increased the allowable storage space and damn near

doubled it. In layman's terms, an E-3 could accumulate worldly goods amounting

to those on par with migrating Mongolians and folks doing life on Devil's

Island.

Next, and this can only be appreciated by an idiot bastard who

ever had the wonderful experience of a surface battery charge in a state five

sea, the damn things hanging down on the passageway side of a berthing

compartment, kept you from being beat to death, bouncing off inanimate objects

bolted to the pressure hull. They serve to pad the piping surrounding the

bunks known as bunk rails. Your ribs were very grateful.

But the best thing about bunk bags was their ability to be

converted into instant short-range luggage... Sort of a 'submariners Samsonite

overnight' bag. By snapping the two center straps together, you could

create what passed for a luggage handle... A poor excuse for a carrying device,

but usable. A bunk bag full of the supplies needed for a 72-hour excursion

into the heartland of the civilian population, was the worst of all possible

choices.

Mentally picture the left leg of a fat woman's panty hose filled

with Jell-O and stitched up at the open end and at midway from thigh to toe,

attach a sea bag handle and you have the most unwieldy AWOL bag ever created and

the ugliest damn contraption ever invented by man... A floppy sausage full of

the meager possessions of a long-range boat bum.

The damn things had one distinct advantage that no other personal

gear conveyance had. If you saw some fleet untouchable standing beside the

highway with one of the fool things at his feet, you knew immediately that the

hitchhiking man was a boat sailor. A fellow submarine sailor would burn

flat spots in a new set of tires, stopping to pick you up.

To every old white-haired diesel boat vet, the words 'bunk bag'

bring a smile to his weather-beaten face. You would find it damn hard to come

across an old petroleum-powered submersible resident who didn't have fond

memories of the worthless s$%%^&*(.

O. R. I.

Preparing for an Operational Readiness

Inspection is a tedious endeavor. The boat is cleaned from stem to stern, then

cleaned again. Each operational procedure is rigidly practiced, time after

time. Every function on a submarine is looked at under a microscope, and

overseen by the captain and executive officer. Then each junior officer relays

commands to the various chiefs. Each chief in his area of responsibilities

grinds the crewmen under his supervision until every job, every procedure and

every function of running a submarine is carried out flawlessly by the crew

members.

The Cusk was ready for this ORI in early

1949. Taking on fuel was our last major chore. Saturday morning we moved from

the nest, and docked at Ballast Point, the Navy Fuel Depot in San Diego harbor.

Most of the crew was on liberty, with

only a small contingent of men left to complete the fueling. Once we had

secured from maneuvering watch, I essentially had no duties. This left me free

to go topside and enjoy the sunshine and fresh air. Soon I was joined by Robert

Hugh MacDowall and we engaged in serious philosophical debate as to the truth

about “B” girls being virtuous.

Robert Hugh (a handsome, tall fellow

with a thick blond curly head of hair) expressed his opinion that the girls he

met on the beach were all upstanding, church going, clean, intellectual ladies.

And, that suited Robert to a tee. I being a shy, retiring young man, and

totally ignorant in the ways of women had to agree with much of what Robert

said, however, since Robert always had a smile on his face. . . . ? I did have

to acquiesce to Robert, because he had emanated from a highly charged cultural

center, known for its gifts of intellectualism to its natives. Akron, Ohio has

an amazing ring of sophistication to it, don’t you think?

Soon we tired of this conversation and

turned to more interesting things. We decided to practice throwing the heaving

line. After all, it was a way to entertain ourselves, and obviously would

benefit us for future line handling duties. Besides, it was fun.

Soon we challenged each other into who

was the best “heavie tosser.” We obtained permission from “Swish” Saunders to

tie a line to a life ring, toss it out and use it as a target. Yes, there was a

small tide, and occasionally we would retrieve the ring, and relocate it.

The lighthearted tossing slowly became

more serious. When two or more men are engaged in this type of game, it sooner

or later develops into “I can beat you” mentality. We began testing our skills

at landing in the middle of the life ring. We added speed to the requirements.

Speed and accuracy became the watchword. Toss the line to the target, reel it

in and toss it again as rapidly as possible, maintaining accuracy as an

important element to the game.

We were observed by everyone who came

topside, and several times we were interrupted by another crewman who would want

to show us how it was done properly. They usually slunk away when they failed

miserably to best us, two highly motivated expert tossers.

After a couple of hours we grew tired,

but we truly did become highly skilled in speed and accuracy. Mack, always the

gentlemen, agreed that he was second best in all categories (even in distance),

but he didn’t know I had been a Sea Scout and had trained for many hours in this

art before joining the Navy. Had we been betting, it would have truly been

taking candy from a baby.

The following week at sea was spent in

working with the inspecting officer from the flotilla, and appeared to have

passed all the ORI events with ease. We headed back to San Diego to tie up and

begin Liberty. But the trials were not completely over. Our ships handling

of the docking procedure were the last of the tests to be performed.

Maneuvering Watch was set. I joined E.

C. Draper in the After Engine Room, after acquiring a cup of hot black spicy

coffee for his lordship, (is Tabasco Sauce a spice or an herb?). Both engines

were running, and being manipulated by the electricians in the Maneuvering Room.

All was normal, when I received word I was to report topside to see Swish.

With a small amount of trepidation I

found Swish forward with the number one line handling unit. Swish informed me

he wanted me to get number one over, as the tide was fierce and they were having

problems coming in close to the outboard boat in the nest. I didn’t have time

to consider the honor bestowed upon me, I dutifully selected a choice heaving

line from the deck locker where they were stowed.

I had time to wet the line and make a

couple of practice tosses before the order to “put number one over” was given.

I refrained from saluting the bridge to acknowledge the order, however I did

spot the Skipper and the ORI officers on the bridge. I sensed our skipper was

telling the commodore I could toss the heaving line a nautical mile. Obviously

the Skipper was counting on me to make a flawless pitch and cap the ORI with

skilled line handling.

Quickly I surveyed our situation. The

bow was swinging away, the distance was great, and fear was showing in the eyes

of all the men in the party. However I was ready. It would take a

championship effort, but I knew I was up to speed to handle the chore. I felt

my muscles tense, my computing brain had figured the wind, the speed, the

distance and the ebbing tide, yes it could be done.

The line was wet, half of the coils were

in my left hand, the remainder in my throwing hand. The line handling party on

the other boat was awaiting the “Monkey Fist.” All eyes were on me, I knew my

chance at a commendation medal was upon me. I wound up, resembling a tightly

coiled spring, took a deep breath and let her go.

The heaving line left my hand with a

flight speed that could have broken the sound barrier. It had the velocity, it

had everything it would take to make the toss successful, that is, everything

but a desire to obey my command. I watched as the leaded Monkey Fist left my

hand and traveled about five degrees from perpendicular. It went straight up

with a slight arc and wrapped itself around the antennae wire running from the

shears to the Bull Nose. It didn’t make a single wrap, it wound around the wire

until all its forces were exhausted. It was perfectly wrapped and locked onto

the wire.

I can still hear the sound of wind

leaving my lungs, followed by a litany of words from my fellow crewmen, words

that would make the devil blush. Words that only serve a purpose when you

strike your thumb with a four pound mall. Words that cannot be printed here.

I didn’t wait to be ordered below. My

instincts told me to retreat to a safer place. My safe haven, the After Engine

Room was awaiting me. Once again the benevolence of Submarine Sailors came into

play. I never heard about the incident again from any of my fellow shipmates.

But to this day, I remember, and through the years this incident has come back

to either haunt or aid me in the realities of life.

In real life, remaining humble takes an

incredible amount of work.

Norm Carkeek 1949-1951

USS CUSK SSG 348

U.S.S. Barb: The Sub that Sank a Train in WW II

In 1973 an

Italian submarine named Enrique Tazzoli was sold for a paltry $100,000 as scrap

metal. The submarine, given to the Italian Navy in 1953 was actually an

incredible veteran of World War II service with a heritage that never should

have passed so unnoticed into the graveyards of the metal recyclers. The U.S.S.

Barb was a pioneer, paving the way for the first submarine launched missiles and

flying a battle flag unlike that of any other ship. In addition to the Medal of

Honor ribbon at the top of the flag identifying the heroism of its captain,

Commander Eugene 'Lucky' Fluckey, the bottom border of the flag bore the image

of a Japanese locomotive. The U.S.S. Barb was indeed, the submarine that 'SANK

A TRAIN'.

July, 1945 (Guam) - Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz looked across the desk at

Admiral Lockwood as he finished the personal briefing on U.S. war ships in the

vicinity of the northern coastal areas of Hokkaido, Japan. "Well, Chester,

there's only the Barb there, and probably no word until the patrol is finished.

You remember Gene Fluckey?"

"Of course. I recommended him for the Medal of Honor," Admiral Nimitz replied.

"You surely pulled him from command after he received it?"

July 18, 1945 - (Patience Bay, off the coast of Karafuto, Japan) it was after 4

A.M. and Commander Fluckey rubbed his eyes as he peered over the map spread

before him. It was the twelfth war patrol of the Barb, the fifth under Commander

Fluckey. He should have turned command over to another skipper after four

patrols, but had managed to strike a deal with Admiral Lockwood to make one more

trip with the men he cared for like a father, should his fourth patrol be

successful. Of course, no one suspected when he had struck that deal prior to

his fourth and what should have been his final war patrol on the Barb, that

Commander Fluckey's success would be so great he would be awarded the Medal of

Honor.

Commander Fluckey smiled as he remembered that patrol. 'Lucky' Fluckey they

called him. On January 8th the Barb had emerged victorious from a running

two-hour night battle after sinking a large enemy ammunition ship. Two weeks

later in Mamkwan Harbor he found the 'mother-lode'...more than 30 enemy ships.

In only 5 fathoms (30 feet) of water his crew had unleashed the sub's forward

torpedoes, then turned and fired four from the stern. As he pushed the Barb to

the full limit of its speed through the dangerous waters in a daring withdrawal

to the open sea, he recorded eight direct hits on six enemy ships. Then, on the

return home he added yet another Japanese freighter to the tally for the Barb's

eleventh patrol, a score that exceeded even the number of that patrol.

What could possibly be left for the Commander to accomplish who, just three

months earlier had been in Washington, D.C. to receive the Medal of Honor? He

smiled to himself as he looked again at the map showing the rail line that ran

along the enemy coast line. This final patrol had been promised as the Barb's

'graduation patrol' and he and his crew had cooked up an unusual finale. Since

the 8th of June they had harassed the enemy, destroying the enemy supplies and

coastal fortifications with the first submarine launched rocket attacks. Now

his crew was buzzing excitedly about bagging a train.

The rail line itself wouldn't be a problem. A shore patrol could go ashore

under cover of darkness to plant the explosives...one of the sub's 55-pound

scuttling charges. But this early morning Lucky Fluckey and his officers were

puzzling over how they could blow not only the rails, but one of the frequent

trains that shuttled supplies to equip the Japanese war machine. Such a daring

feat could handicap the enemy's war effort for several days, a week, perhaps

even longer.

It was a crazy idea, just the kind of operation 'Lucky' Fluckey had become

famous...or infamous...for. But no matter how crazy the idea might have

sounded, the Barb's skipper would not risk the lives of his men. Thus the

problem... how to detonate the charge at the moment the train passed, without

endangering the life of a shore party.

PROBLEM? Not on Commander Fluckey's ship. His philosophy had always been

"We

don't have problems, only solutions".

11:27 AM - 'Battle Stations!' No more time to seek solutions or to ponder

blowing up a train. The approach of a Japanese freighter with a frigate escort

demands traditional submarine warfare. By noon the frigate is laying on the

ocean floor in pieces and the Barb is in danger of becoming the hunted.

6:07 PM - Solutions! If you don't look for them, you'll never find them. And

even then, sometimes they arrive in the most unusual fashion. Cruising slowly

beneath the surface to evade the enemy plane now circling overhead, the monotony

is broken with an exciting new idea.

Instead of having a crewman on shore to trigger explosives to blow both rail and

a passing train, why not let the train BLOW ITSELF up.

Billy Hatfield was excitedly explaining how he had cracked nuts on the railroad

tracks as a kid, placing the nuts between two ties so the sagging of the rail

under the weight of a train would break them open. 'Just like cracking walnuts,'

he explained. 'To complete the circuit (detonating the 55-pound charge) we hook

in a micro switch ..between two ties. We don't set it off, the TRAIN does.' Not

only did Hatfield have the plan, he wanted to be part of the volunteer shore

party.

The solution found, there was no shortage of volunteers, all that was needed was

the proper weather...a little cloud cover to darken the moon for the mission

ashore. Lucky Fluckey established his own criteria for the volunteer party: No

married men would be included, except for Hatfield...The party would include

members from each department...The opportunity would be split between regular

Navy and Navy Reserve sailors... At least half of the men had to have been Boy

Scouts, experienced in how to handle themselves in medical emergencies and in

the woods....FINALLY, 'Lucky' Fluckey would lead the saboteurs himself.

When the names of the 8 selected sailors was announced it was greeted with a

mixture of excitement and disappointment. Among the disappointed was Commander

Fluckey who surrendered his opportunity at the insistence of his officers that

'as commander he belonged with the Barb,' coupled with the threat from one that

"I swear I'll send a message to ComSubPac if you attempt this (joining the shore

party himself)." Even a Japanese POW being held on the Barb wanted to go,

promising not to try to escape.

In the meantime, there would be no more harassment of Japanese shipping or shore

operations by the Barb until the train mission had been accomplished. The crew

would 'lay low', prepare their equipment, train, and wait for the weather.

July 22, 1945 - (Patience Bay , Off the coast of Karafuto, Japan) Patience Bay

was wearing thin the patience of Commander Fluckey and his innovative crew.

Everything was ready. In the four days the saboteurs had anxiously watched the

skies for cloud cover, the inventive crew of the Barb had built their micro

switch. When the need was posed for a pick and shovel to bury the explosive

charge and batteries, the Barb's engineers had cut up steel plates in the lower

flats of an engine room, then bent and welded them to create the needed tools.

The only things beyond their control was the weather....and time. Only five

days remained in the Barb's patrol.

Anxiously watching the skies, Commander Fluckey noticed plumes of cirrus clouds,

then white stratus capping the mountain peaks ashore.

A cloud cover was building to hide the three-quarters moon. This would be the

night.

MIDNIGHT, July 23, 1945 - The Barb had crept within 950 yards of the shoreline.

If it was somehow seen from the shore it would probably be mistaken for a

schooner or Japanese patrol boat. No one would suspect an American submarine so

close to shore or in such shallow water. Slowly the small boats were lowered to

the water and the 8 saboteurs began paddling toward the enemy beach.

Twenty-five minutes later they pulled the boats ashore and walked on the surface

of the Japanese homeland. Having lost their points of navigation, the saboteurs

landed near the backyard of a house. Fortunately the residents had no dogs,

though the sight of human AND dog's tracks in the sand along the beach alerted

the brave sailors to the potential for unexpected danger.

Stumbling through noisy waist-high grasses, crossing a highway and then

stumbling into a 4-foot drainage ditch, the saboteurs made their way to the

railroad tracks. Three men were posted as guards, Markuson assigned to examine a

nearby water tower. The Barb's auxiliary man climbed the ladder, then stopped

in shock as he realized it was an enemy lookout tower....an OCCUPIED tower.

Fortunately the Japanese sentry was peacefully sleeping and Markuson was able

to quietly withdraw and warn his raiding party.

The news from Markuson caused the men digging the placement for the explosive

charge to continue their work more slowly and quietly.

Suddenly, from less than 80 yards away, an express train was bearing down on

them. The appearance was a surprise, it hadn't occurred to the crew during the

planning for the mission that there might be a night train. When at last it

passed, the brave but nervous sailors extricated themselves from the brush into

which they had leapt, to continue their task. Twenty minutes later the holes

had been dug and the explosives and batteries hidden beneath fresh soil.

During planning for the mission the saboteurs had been told that, with the

explosives in place, all would retreat a safe distance while Hatfield made the

final connection. If the sailor who had once cracked walnuts on the railroad

tracks slipped during this final, dangerous procedure, his would be the only

life lost. On this night it was the only order the saboteurs refused to obey,

all of them peering anxiously over Hatfield's shoulder to make sure he did it

right. The men had come too far to be disappointed by a switch failure.

1:32 A.M. - Watching from the deck of the Barb, Commander Fluckey allowed

himself a sigh of relief as he noticed the flashlight signal from the beach

announcing the departure of the shore party. He had skillfully, and daringly,

guided the Barb within 600 yards of the enemy beach. There was less than 6 feet

of water beneath the sub's keel, but Fluckey wanted to be close in case trouble

arose and a daring rescue of his saboteurs became necessary.

1:45 A.M. - The two boats carrying his saboteurs were only halfway back to the

Barb when the sub's machine gunner yelled, 'CAPTAIN! Another train coming up

the tracks!' The Commander grabbed a megaphone and yelled through the night,

'Paddle like the devil!', knowing full well that they wouldn't reach the Barb

before the train hit the microswitch.

1:47 A.M. - The darkness was shattered by brilliant light and the roar of the

explosion. The boilers of the locomotive blew, shattered pieces of the engine

blowing 200 feet into the air. Behind it the cars began to accordion into each

other, bursting into flame and adding to the magnificent fireworks display.

Five minutes later the saboteurs were lifted to the deck by their exuberant

comrades as the Barb turned to slip back to safer waters. Moving at only two

knots, it would be a while before the Barb was into waters deep enough to allow

it to submerge. It was a moment to savor, the culmination of teamwork,

ingenuity and daring by the Commander and all his crew. 'Lucky'

Fluckey's voice came over the intercom. 'All hands below deck not absolutely

needed to

maneuver the ship have permission to come topside.' He didn't have to repeat

the invitation. Hatches sprang open as the proud sailors of the Barb gathered

on her decks to proudly watch the distant fireworks display. The Barb had

'sunk' a Japanese TRAIN!

On August 2, 1945 the Barb arrived at Midway, her twelfth war patrol concluded.

Meanwhile United States military commanders had pondered the prospect of an

armed assault on the Japanese homeland. Military tacticians estimated such an

invasion would cost more than a million American casualties. Instead of such a

costly armed offensive to end the war, on August 6th the B-29 bomber Enola Gay

dropped a single atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. A second such

bomb, unleashed 4 days later on Nagasaki, Japan, caused Japan to agree to

surrender terms on August 15th. On September 2, 1945 in Tokyo Harbor the

documents ending the war in the Pacific were signed.

The story of the saboteurs of the U.S.S. Barb is one of those unique, little

known stories of World War II. It becomes increasingly important when one

realizes that the 8 sailors who blew up the train at near Kashiho, Japan

conducted the ONLY GROUND COMBAT OPERATION on the Japanese 'homeland' of World

War II. The eight saboteurs were:

Paul

"Swish" Saunders

(Cusk COB, 1950),

William

Hatfield, Francis Sever, Lawrence Newland, Edward Klinglesmith, James Richard,

John Markuson, and William Walker.

NOTE: Eugene Bennett Fluckey retired from the Navy as a Rear Admiral, and wears

in addition to his Medal of Honor, FOUR Navy Crosses... a record of awards

unmatched by

any living American. In 1992 his own history of the U.S.S. Barb was published in

the award winning book, THUNDER BELOW. Over the past several years proceeds

from the sale of this exciting book have been used by Admiral Fluckey to provide

free reunions for the men who served him aboard the Barb, and their wives.

Admiral Fluckey was born in Washington, D.C. in 1913 and graduated from the

U.S. Naval Academy in 1935. He died 28 June 2007 in Annapolis, Maryland.

- - - -

And you know what? We still make 'em like we use to!

The Puppy by Sam Lyons

The Cusk went on a

WestPac cruise

(about) 1954. We visited several places but on the last night of liberty in one

of the Japanese ports, we were leaving and going to another location. One of the

"Iron heads" from the After Engine Room came back aboard with a cute little

pup. Of course the Skipper had warned all of us about bringing back any thing

that was unauthorized and this fit the bill. Both the enginemen and electricians

kept mum about the pet for just long enough so that it couldn't be put ashore.

So one of the officers found out about it and the Captain was fit to be tied.

Anyway, to make a long story short, we were to keep it in the engineering spaces

until we could off load it on the beach. Since the after engine room was so hot

and noisy we wound up with it in the Maneuvering Room. Well, what do you do

with a dog at sea when it gets the call of nature? What we did was train the

pup to stay in it's box in Maneuvering Room until it wanted to take a dump or

water the lilies. Then we would let the Engineman have it to pet and play with

until after the call of nature, then the pup would come to the hatch opening

between Maneuvering and the After Engine Room and want to come back to us. When

we pulled into port we gave it to one of the "bum boats" that use to come along

side. It was a good thing that we did because it was coming down with the

"mange"

Air Power - by Norm Carkeek

Some time ago, I had reason to send

this story to NAVSEA, to make a point on a problem in which we were mutually

involved. Follows a simple sea story, after 47 years facts become dimmed, (but

it is a true story).

The USS Cusk (SSG-348), somewhere

in the Pacific, very early 1950. Our mission was to carry a group of 35 US Army

map makers to a beach prior to a landing. We carried three large inflatable

rubber rafts, and all of their equipment, stored in the “Loon” hanger, on deck

aft of the top side superstructure. This was the first trip aboard a submarine

for this Army unit. The additional men were assigned to the forward torpedo

room, the after battery and the after torpedo room. They immediately learned

the term of “hot bunking”.

We cruised submerged during the

daylight hours, an surfaced at twilight. At that time we aired the boat,

charged batteries, and made speed. One side note, the Army contingent was

pleased they were not allowed to shower during this cruise. After steaming for

several days, it was time to make our submerged run as dawn was approaching. At

approximately 0500 hours, the order was given to dive the boat.

At this point flooding of all

tanks was performed. However, due to the on duty diving officers error in

miscalculating the weight forward (estimated at 10,000 pounds heavy), the boat

assumed an incredible down angle. Since we lost both bubbles in the control

room we never knew for sure the exact degree, but the crew was sure we exceeded

45 degrees.

The diving officer gave the

command to blow all tanks which had been flooded to effect the dive. The down

angle prevailed, and seemed to get worse. At this point, anything that was not

tied down moved toward the angle of the dive, this included our prized stainless

steel garbage cans in the crews mess. The condensate collected from the

ventilation system spilled onto the deck.

I was sleeping in the top bunk

starboard side aft in the after battery. My head was placed approximately

three inches from a vent valve minus the handle. I looked over at Pappy Donovan

(EN1) who always had a wad of snuff packed in his lower lip (even when

sleeping), who sat upright and swallowed his cud. I knew then we were in

trouble.

Without hesitation, all crewmen

not on dive watch began an orderly, but with serious energy, movement aft. The

G. I. contingent had no idea as to the events taking place, and were dragged

along with the crewmen. The water on the deck required extra effort to move

over. The watertight door between the after engine room and the after battery

was closed and battened down. I would estimate the weight of the door at over

two hundred fifty pounds. We succeeded in opening the door, with the help of

the forward engine room oiler who was standing on the bulkhead and pulling as we

pushed.

The diving officer ordered

emergency reverse. The engines had been shut down during the diving procedure,

which left us using the batteries for power. The boat was vibrating with

incredible intensity as the screws were rotating. As I passed through the

maneuvering room, one of the electricians shouted out “four hundred and eighty”,

or some other impressive number. Naturally, I presumed he was monitoring our

depth. However, he was reading the turns on the screws.

Every man not on dive watch was

crammed into the after torpedo room, this of course included the Army

contingent. They still did not have any information as to what was happening,

as the boats crew acted entirely stoic, but with precision acquired from

countless hours of training.

Finally, the boat righted with a

resounding crashing noise.

It seems we were hung up on the

surface. The bow was down about one hundred and fifty feet. The stern was

above water, and the screws were fanning air This entire event took place in a

very few short minutes. The visitors were dumbfounded, but finally were given

some education about what a submarine does, and how it does it. All men aboard

that boat acted in a totally controlled, and intuitive manner. Added was an

element of common sense.

Without any further ado, we

completed our mission. The GIs were very happy to leave the boat. And the

subject only was rarely brought up again, except to make a point with a new

crewman.

Hot, Not Exactly Straight, and Abnormal

by Tom Roseland

During what turned out to be the

Cusk's final WestPac in January of 1969, we fired an exercise shot fired at a

Canadian destroyer while patrolling off the coast of Vietnam. Mostly due to

the fact that it was a "recycled" fish off the tender, it went awry and came

back at us almost as soon as it left the tube. Instead of drawing left toward

the Canadian, the fish began to circle toward the right almost as soon as she

left the tube. As it began to close on us, the call for "Emergency Deep, Use

Negative!" sent the Cusk to 200 feet so quickly it caused an air conditioning

cooling line to explode. No sooner had we reached 200 feet when the collision

alarm sounded followed by the words, "Flooding in the Engine Room, Flooding in

the Engine Room!" blaring on the 1MC. Three quick blasts from the claxon

mandated an emergency surface and we rose quickly just as the malfunctioning

torpedo passed by. No damage was sustained and the errant torpedo was later

recovered and returned (happily) to its previous owners aboard the tender in

San Diego.

The Paint Job by Ken Van Hoy

"...His nickname was 'Stratts".

I can still remember him assigning me to scrape out the air boxes in #3 main

engine during an overhaul. I worked with another Engineman named Bradford to

clean it out. I think I still have some of the carbon grit in my pores. I also

remember a time I was assigned some special duty to paint the deck one night of

a work barge we were staying on during dry-dock. He gave me five gallons of

green decking paint and a paint brush. I quickly determined it would take all

night with the brush he gave me, so I found a broom and used it and was finished

in no time. The next morning he asked me how I was able to finish so quickly.

I never told him about the broom. He probably still thinks I'm the world's

fastest painter.

Operation Iceberg by Don Boberick, RM3(SS), with the invaluable collaboration of Ernest “Zeke” Zellmer, Lieutenant, U.S.N.

This is a story from two old

sailors about the participation of United States submarines Cusk (348) and

Diodon (349) in “Operation Iceberg” - An expedition by four submarines to Alaska

and beyond - during July and August 1946. I [Don Boberick] told some of this

story before in the USS Cusk Newsletter of a couple of years ago. It happens

that during this arctic cruise I was aboard Diodon, having transferred from Cusk

to Diodon earlier in the year. The fact that I was actually on Diodon is of

little importance to this piece of Cusk history, as both submarines traveled

together throughout the cruise and what one boat did the other did also or at

least was a percipient witness. Since the time I first related this story, its

depth has been enlarged and its accuracy enhanced through the benefit of some

recollections from the wardroom of the Cusk, courtesy of Ernest “Zeke” Zellmer,

who was the Cusk’s Engineering Officer at the time. Any full recounting of the

story of the Cusk’s arctic cruise must contain a diversion or two about

incidents that were not part of the original ComSubPac script and are each a

story in their own right. The titles of these extra curricular adventures might

be “The Dutch Harbor Cumshaw Caper” and “Columbia Glacier - The Errant Torpedo.”

Part I

Cusk and Diodon left San Diego in

late July, destination Kiska Island in the western Aleutian Island chain. The

original sailing orders called for a rendezvous at Kiska Island with the

submarines Blackfin and Trumpetfish, which were sailing from Pearl Harbor.

Instead of proceeding all the way to Kiska, the rendezvous destination was

changed to the U.S. Army facility at Dutch Harbor, on Unalaska Island - which is

located not nearly as far to the west as Kiska would have placed us. En route

from Pearl Harbor the Admiral aboard Blackfin, who commanded the expedition,

received orders to keep the expedition east of the International Dateline and of

the Russian land mass. This was apparently due to some elevated political

unrest between the U.S. and the USSR at the time. Eventually all four boats

arrived alongside Dutch Harbor’s single wharf, with Cusk the inboard boat.

After a brief but eventful (as I will later explain) repose at Unalaska, the

boats departed en masse and formed up in the Bering Sea preparatory to sailing

north toward the Bering Strait and polar ice cap beyond.

One of Zeke Zellmer’s lasting

recollections of this early part of the cruise is having to carry-off, as

Officer-of-the-Deck on Cusk, a series of surface-Navy maneuvers that he had not

before been obliged to perform in a submarine. It seems that our Admiral had

not lost his “surface Navy” roots. When the four boats first formed up in the

south Bering Sea and started north, they took up a line-astern formation. Later

that afternoon the Admiral, who was still on the Blackfin at the time,

dispatched an order to all boats to change formation to one of line-abreast.

(Perhaps it was to present a more formidable appearance or just a case of having

fun with these submarine sailors?) For the first time since his days at the

Academy, Zeke had to quickly work out a maneuvering board exercise to get the

course and speed for the Cusk’s new station. Cusk had been directed to take

station out on the extreme wing. He was certain the Admiral would take a dim

view of the Cusk were it to be observed zigging and zagging into its new

position. The Admiral would expect no more (or no less) than a one course and

one speed change in order to get into position and then a quick return to base

course and speed. Zeke executed the maneuvers without incident but remained

apprehensive of what maneuvering the Admiral might next call for and was glad

when his relief arrived.

The expedition group stopped

briefly offshore at the Pribilof Islands near the village of St. George.

Sometime during the trip north through the Bering Strait, the Admiral

transferred his flag to the Cusk. About the only memory I have of Diodon’s

northward traverse of the Bering Sea is that we constructed and flew several

metal framed box kites as radio antennas and also gathered a number of sea

bottom samples with specially fabricated containers. I had no idea as to the

purpose of these activities. Upon arriving at the southern edge of the polar

ice cap, somewhere above latitude 72° North, the Cusk made a dive and, I

thought, conducted a short sojourn under the ice pack. Zeke concurs that Cusk

dove at this location all right but says she did not go beneath the ice cap.

Zeke tells that part of the mission of the trip was to reconnoiter the Wrangel

Islands, which are considerably north of the Arctic Circle and far from any U.S.

territory. This plan was, however, scrubbed after receipt of the message to

remain clear of Russian waters. I am glad this planned action was scrapped as

those Islands are in an isolated section of the Chukchi Sea and they belonged to

the USSR. The Russians coincidentally kept us under radar surveillance much of

the time we were north of the 68th Parallel. As I recall we all remained near

the ice cap overnight. Next morning all boats departed to the south. It was

very foggy at the beginning of the trip southward. On Diodon, we were using

radar to plot the locations of some of the Russian defense radar facilities,

which we could readily detect by the lines of electronic interference shown on

our own radarscope. Somewhere between 70° & 71° North, Diodon’s surface search

radar detected a target proceeding directly toward us on a northeasterly

course. We confirmed the target with the Cusk who also had picked up the target

on their radar. At first, we suspected that it was some kind of an ocean patrol

craft as its speed was in the neighborhood of 20-25 knots. The target continued

to head towards the Diodon until it reached a point less than a mile distant.

We could not observe anything visually because of the fog. The target then

reversed its course and proceeded to exit the area at an estimated speed of

sixty knots. We know that in 1946, no sea going vessel could attain a speed of

60 knots and no fixed wing aircraft could fly as slow as 25 knots. So, what was

it? It was too far from land to be one of the rudimentary helicopters of that

era. It was not a sea going surface craft of any known type. Was it a blimp or

dirigible operating above the fog layer? We never learned its true nature or

origin, nor did we even confirm that it was indeed anything more than an

unidentified image on our radarscopes. It sure looked and behaved, however,

like something that was real.

The group continued southward

through the Bering Strait, passing slightly east of the Diomede Islands. It is

at these islands where a distance of less than two miles separates United States

and Russian soil (and the inhabitants of both islands fraternize back and forth

without the niceties of passport or entry visa). Somewhere around Cape Prince

of Wales, the western most extension of the Territory of Alaska, Cusk and Diodon

left the company of the Hawaii boats and took up a course southeast to the town

of Nome, Alaska. (There is a wonderful old poem, “Nome Town, My Home Town,”

that paints a much prettier picture of this small city than it truly deserves)

Part 2

Cusk and Diodon arrived off Nome,

Alaska, early the next morning. Both boats anchored about a mile from shore, as

Nome’s small harbor was only sufficient for shallow draft fishing boats. Some

ship’s personnel were given a few hours liberty in the town and were ferried by

small open boat from ship to shore. I remember that I slipped ashore on one of

the ferry runs without permission and got caught coming back aboard that

afternoon. Nome in those days had very little to offer except a few bars along

Front Street (a dirt street with wooden sidewalks) and native handicraft for

sale at the Post Office. One of those bars was named “Arctic Bar” (What else?)

The Arctic Bar is still there, in the same location, and remains one of those

attractions that tourists consider a must place to visit while in Nome. The

principle differences between 1946 and today is that there are several more such

establishments in town, including one with a small hotel. In addition, the

sidewalk in front of the Arctic Bar is now concrete with (at various times

depending upon the existent mood of the city counsel) a couple of parking meters

adjacent to the curb - and there are a lot more people now. The Cusk and Diodon

crews did not do themselves proud in Nome. Many became more than just

inebriated. I remember two or three of the Diodon crew trying to “borrow” an

old flatbed truck that was standing in someone’s yard, in order to provide

themselves with a ride down to the docks. These characters got the truck

running and proceeded to drive it a couple of blocks before crashing it ever so

slightly it into the side of a building close to the wharf. At some point

before all the liberty goers were returned to their respective boats, a fight

broke out on the wharf between members of the two crews. I do not remember how

it got started but it was a “Cusk vs. Diodon” issue of some kind. Both subs

left Nome in the late afternoon for their next stop at Kodiak, Alaska. After

Kodiak, it was northeast into Prince William Sound for a visit to Seward,

Alaska. In Seward, we berthed both boats at the Army dock and again crews were

afforded shore liberty. The main street of Seward (unpaved then) was just a

couple of blocks walk from the dock. The location where the boats docked in

1946 was later destroyed in the 1964 earthquake and is now little more now than

the remnants of a crumbled seawall. (To my knowledge the most recent visit to

Seward by a submarine was the USS Alaska which stopped there with its Blue Crew

over the July 4th holidays in 1987.) After a day in Seward, Cusk and Diodon

departed for Columbia Bay on the eastern side of Prince William Sound close to

the town of Valdez, which is now the southern terminus of the Alaska oil

pipeline. Columbia Bay was carved out by the Columbia Glacier, which is over

forty miles long and has its terminus, then and now, at the northern end of this

wide fjord. Because it terminates in an ocean inlet Columbia is the most

spectacular alpine glacier to be seen in the world. This excursion of Cusk and

Diodon to the Columbia Glacier was to prove to an adventure of its own.

Part 3 and “Columbia Glacier - The

Errant Torpedo”

Cusk and Diodon entered Columbia

Bay in mid afternoon of a typical August day in South-central Alaska high

overcast and temperatures in the sixties. The mission was for Diodon and Cusk

to fire live Mark V electric torpedoes across the bay toward the one hundred

foot high and four mile wide face of Columbia Glacier. Columbia Glacier

deposits thousands of tons of ice each summer day into the bay. This occurs as

the warmer sea water melts the submerged portion of the glacier’s face and the

ice calves off into the bay to float away as small icebergs. Zeke explains that

the reason for firing the torpedo was to test, in that ice cube filled water,

how well the WWII electric torpedoes would function in the cold environment.

Certainly, today, firing a torpedo at this alpine glacier would not be permitted

or even considered in light of pristine environment of the glacier and its

surrounds. I was on the Diodon when this took place and was topside at the time

of the torpedo launch. At this point, I return to the recollections of Zeke

Zellmer, who witnessed the incident from the bridge of the Cusk. Diodon

launched the Mark V torpedo from their stern tubes. The launch of the torpedo

was in the direction of the glacier - directly toward the sixty foot tall face.

As this was an electric torpedo, there was no visible wake. To those of us

watching from the topside positions nothing was happening - we were just

watching and waiting with an expectation of seeing a large explosion and a

scattering of ice when the torpedo struck the glacier. We watched and we

waited. We waited and we watched. Nothing! Then we noticed that the Cusk was

backing emergency and rapidly moving away. We soon learned that Cusk’s sonar

had reported the torpedo making a circular run counter clockwise toward the

west. On Diodon, we must have lost track of the torpedo because we continued to

watch for impact against the face of the glacier - but nothing happened. No

explosion was heard or felt and it was far past the time that impact was

supposed to have taken place. While some were speculating that it might have

been a dud, the bridge nevertheless put on emergency power to “get the hell out

a here.” Then when those persons topside least expected it, there was an

explosion several thousand yards to the east of our position at the site of

gravel spit (an old lateral moraine) that extended southward from the glacier.

Zeke, on Cusk, says the Admiral ordered “End of Exercise.” We departed the area

with most of us on Diodon convinced that the torpedo had completed a circular

run around the boat before it impacted against the gravel spit. The force of

the explosion must have been directed harmlessly upward into the atmosphere,

which was perhaps for the better. An explosion of that magnitude against the

face of the glacier would have generated tremendous forces downward and seaward

of the face where the waters abound with marine mammals - seals, sea lions and

sea otters primarily, with an occasional pod of killer whales in the area.

Later the experts speculated that cold water (in the tube before the firing as

well as in the bay where the torpedo was running) caused the lubricants to

become so viscous that the rudder froze in a hard over position. The torpedo

apparently required some running time to allow the motor heat and vibration to

free up the rudder and let it try to get back on course.

From Columbia Bay, both boats

sailed south through Prince William Sound and into the Gulf of Alaska to began

the journey homeward. Both vessels diverted over to Juneau, the Capital of

Alaska, for a visit and a day in port. The next day both headed southward

through portions of the Inland Passage of Alaska’s southeastern archipelago and

home. The traverse of the Inland Passage was foreshortened to just one day and

a night due to constant fog, which made navigating all of those Islands too

torturous a task. The boats headed for deep water and a faster trip home.

Part 4 - “The Dutch Harbor Cumshaw Caper”

At the beginning of my recounting

of this cruise, I spoke of an episode worthy of telling by itself - the cumshaw

caper. What this is about is the activity of several crews while at the group’s

rendezvous at Dutch Harbor. Dutch Harbor, on Unalaska Island, was the site of

United States Army, Air Corps and Navy activity during World War II. It was one

of the major U.S. outposts in the Aleutian Island chain, which stretches

westward beyond the International Dateline. There were some military facilities

farther west but those bases were much smaller than those of Dutch Harbor. The

arrival of the Cusk, Diodon, Blackfin and Trumpetfish was in late July of 1946

and the military facilities at Dutch Harbor were being mothballed. Navy

activity was completely shut down and all of the Navy’s old equipment and stores

were housed in three warehouses along a Spit where the Navy dock was. This was

in turn less than a mile from the Army base, which still had some limited

operations and a full Colonel in command. Some of the sub sailors could not

suffer the idea of all this gear and equipment going to waste and destined only

for return to the States as surplus hardware. A bit of scouting around on the

day before the arrival of the Pearl Harbor boats had pretty much reconnoitered

where the choicest of the goodies were stored. They could be had for the asking

as long as the Army MPs on base patrol did not get nosy. Some enterprising

crewmember had managed to obtain the loan of a Jeep. Besides the Jeep, there

were several hand held walky-talkies available from the boats. With a well

organized system, the Jeep and two lookouts patrolled along the Spit and back

toward the Army base, keeping eyes open for any sign of the MPs on patrol. In

the meantime, other crewmembers operated inside the warehouses gathering up what

hardware and equipment was of interest and placing it near the entry door. The

use of the Jeep and the radios to warn those inside of any approach of an MP

patrol worked to perfection - they passed by on patrol with no sense that anyone

was inside the warehouses. In one of the warehouses, it was all Navy gear and

included some deep-sea diving equipment such as helmets and rubber suits. In

another of the warehouses nearer the Navy dock (and the submarines) there was

some fancy mess gear that could be utilized. In a third warehouse there were a

lot of radio spares and a lot of “radiosondes” which were used for on weather

balloons for sending back radio signals. What useful purpose they could serve

on a submarine I do not know but we had to steal some anyhow. Every boat

managed to get hold of some of this free for the taking booty. What most of us

did not know was that several Torpedomen from the Blackfin and Diodon had come

across several leather upholstered office chairs at the Army's Headquarters

building and had purloined two of them for use in the torpedo rooms. They found

that the chairs would not go down the hatchways in one piece. Thus, they partly

disassembled them in order to get them below decks where they were reassembled.

The next morning all boats were due to sail north and continue the expedition.

About 0900 all the boats had the main engines running and were ready to cast off

one by one. Suddenly down the road from the direction of the Army base there

appeared one of those Olive drab painted 1942 Ford 4-door sedans headed in our

direction. The car pulled up to the dock and an apparently exited Bird Colonel

demanded to talk to the skippers of all of the submarines - who were on their

respective bridges ready for getting underway. It seems that the Colonel’s

office was missing two leather chairs and he wondered if somehow they had walked

off and found their way over to one or more of the submarines. I understand

that the boat's several skippers assured the Colonel that their crews had not

taken the chairs but that an inquiry and inspection of the below decks would be

undertaken anyway. They did not have to investigate very far as the culprits

came forth voluntarily. So, everyone stayed right in place for more than an

hour while the Torpedo divisions on two boats disassembled each chair enough to

get them up the hatches and then undertook to reassemble each one on deck for

return to the Army. I am not sure whether the commanding officers involved were

upset about the incident or were really amused by the whole thing. I understand

there were some restrictions meted out to the guilty in the torpedo sections.

What was fortunate for some other crewmembers was that the cumshaw of other

material was not discovered and no one ever got into trouble over that aspect.

I have always been able to bring up smile when I think back to those several

sailors inside the warehouses gathering up their loot to be picked up at the

door while a Jeep cruises around outside performing lookout duty. That image is

topped only by recollecting the vision of four United States submarines holding

forth from their scheduled sailing while several sailors are on deck screwing on

the legs and re-securing the leather covers to a couple of stolen chairs.

That is the end of our story but not of

the memories.

A Last Look by Tom Roseland

Home on leave and basking in the hot Texas sun at my home in the hills north of

San Antonio, and unexpected phone call came from, of all places, my boat.

It was Leo Morrissette, the Cusk's yeoman, calling me from the Control Room of

the Cusk in San Diego.

"This

is a surprise, Leo. What's wrong, we going back to WestPac early?", I

asked.

"No,

Tom, I'm just checking to see if you still want that 'early out' that we talked

about.", he responded.

"Yeah,

I do, but my enlistment doesn't expire until March 28th, and I thought I

couldn't get out any earlier than January. Why would you need to know now

in July?"

He

sounded a little surprised. "You haven't heard, have you", he confirmed in

a somewhat amused voice. "We've been decommissioned and the entire crew is

being reassigned, or they're being discharged. Since your enlistment

expires within six months of our decommissioning date, it means you can get out

now if you want to."

"NOW!?! You mean like, right away?!?", I asked incredulously.

"Yep,

as soon as you can get back to San Diego", he responded. "You have a

choice of getting out right away, or getting reassigned to another boat until

your enlistment expires. You want to think about it and call me back?"

"Yeah,

sure, I'll call you back tomorrow, I guess.", I said in what must have been a

stunned voice. I hung up the phone and stared out at the barn and the

water trough where 'Ol Sam was ambling up for an afternoon drink. It just

didn't seem real. I was getting out, now? I had been in for not

quite three and a half years and just wasn't ready for such a shock. And

then it hit me even harder. "The Cusk is being decommissioned?!?", I

thought to myself. "How, why?"

She'

was a perfectly good submarine, renown for having never missed a mission, having

just proven her skill and daring on a recent cold/Vietnam war patrol. Such

a rich history, so many great accomplishments, including being the first

submarine to launch a missile. It just didn't make sense that they could

suddenly, perhaps callously, discard her like that.

And

the crew was being dispersed! So many good friends, for so many years.

Now they were being scattered to the winds. It was all such a surprise.

Most guys get months to plan what they're going to do when they get out. I

didn't get that luxury and it was difficult to grasp. Slowly, I rose went

outside where I sat on the swing under the trees and tried to take it all in.

About

three weeks later, I'm still, trying to take it all in. The Cusk had left

San Diego for Hunter's Point a week earlier and I had stayed behind to go

through my out-processing at the 32nd Street Naval Station. Now I was

heading up Highway 101 to San Francisco in Sandy Whitaker's '63 Chevy. He

had asked me to drive it up so he would have a car in San Francisco. I had

agreed and planned to fly home to Texas from there. No hurry. I had

60 days of leave in my pocket and no particular place to go.

The

memories of the past three years aboard the Cusk continued to flood my mind as I

drove, hour after hour. I thought about laughter and fun times with so

many good friends, that time we hung from those giant buoys for 34 hours and no

fresh air in Bangor, that time when we were at test depth and a valve exploded

in the forward torpedo room, drinking my dolphins at the "Starlight Bar" in

Yokosuka, getting caught and attacked by the Chi-Coms, running into the pier at

White Beach, riding out back-to-back typhoons on two engines in the Eastern

China Sea, diving sideways because someone forgot to open the emergency vent on

the #4 starboard ballast tank, losing and then finding those Marines off San

Clemente, and those days after monotonous, endless days, rolling gently along as

we criss-crossed the great Pacific. Jo-sans and short-times, diesel

flame-outs, CO2 headaches, swim call, funny-money, the laundry truck, weekly

showers...I felt as if I had crammed twenty years of adventures into my three

years aboard the Cusk, and probably had. I knew those memories would never

leave me. I didn't know they would grow more precious over time.

Finally

arriving at Hunter's Point a few days later, I called the boat from the guard

shack and Sandy came out to escort me to the Cusk.

We started immediately talking about the future for both of us and what it might

bring, but soon found ourselves reminiscing about our years aboard the Cusk.

Suddenly, we were at the pier and Sandy was parking the car, but I wasn't

prepared for what I was about to see.

At

first I just sat there staring at the boat, then I slowly got out and continued

staring. I felt like someone who had come home from work only to find

their home in ashes. With her ballast tanks dry

and bereft of all

her fuel, and with much of her equipment removed, the Cusk sat grotesquely high

in the water looking more like a rusty abandoned barn than a submarine. Across

her deck ran scores of hoses, wires, cables, empty pallets, boxes, and other

miscellaneous items.

On the pier under a make-shift shed sat several cases of

beer along with various tools. Every once in a while, "Lani Moo" would get up

and open a huge bottle of Freon and pour it over a six pack to cool it off for a

waiting crewman.

"Want a really cold beer?" Lani

asked with a smile as I walked up.

"Sure", I responded. I sat for a

while drinking my beer and watched as the fathometer was hauled out through the

After Battery hatch and sat on the pier. Then I talked a bit one last time to

some old friends and went below to say good-bye to the COB and the XO. I

emerged about an hour later, looked about, and then told Sandy it was time for

me to go home.

We walked together down the pier

toward his car and at the end of the pier, I stopped and stared back at the Cusk

one last time. "What a sad end to a grand old lady", I thought. Suddenly I

felt like I knew what it must feel like for people to watch their homes burn

down. But then I thought, she took good care of us, did everything we asked her

to do, and she left some enduring and rather impressive history in her wake. It

was good to have been a part of her.

As we drove away, I found myself

wishing I had taken a last picture. But then again, I'm glad I didn't.

What Grandpa did during the Cold War

- from the memoirs of Billy Hrbacek

The

following is an excerpt from a narrative titled ‘What Grandpa did during the

Cold War’ written by Billy P. Hrbacek CWO3 (SS), USN Retired for his

children and grand children. Hrbacek served in submarines or submarine related

duty for 18 of his 25 years of active duty US Navy.

USS CUSK (SS 348) Oct 1959-Jun

1961

The Cusk was formerly a

Guided Missile submarine outfitted with a bulbous topside tank to allow carrying

and launching two Loon type missiles. Cusk was commissioned just before

the end of WWII and saw no war time service. In the late forties and early

fifties she performed duties to prove the possibility of a submarine launched

missile. Most of these exercises were conducted around Pt Mugu, Ca.

Cusk was in fact the first submarine to successfully launch a missile from her

deck. The Loon missile she launched was essentially an updated version of

the German V-1 “Buzz Bomb”. Later in the fifties the hanger was removed

and the boat was re-equipped to be a relay or terminal guidance boat for the

Regulus I and subsequently the Regulus II radar guided missiles both forerunners

of the current cruise missile family of weapons. The Regulus I and II

missiles were both capable of carrying nuclear warheads.

Cusk was my first submarine duty station. I reported aboard in

late Oct 59 as an ETSN, the boat was preparing for overhaul at the Pearl Harbor

Hi. Naval Shipyard. The CO was LCDR Mawhiney who was placed in command shortly

after my having reported onboard. The XO was LCDR Murphy.

At my check in with the COB TMC Atha, I was given an overview of

upcoming events, my qualification check off card and some advice. Of note he

asked if I drank. Being curious I asked him why he was asking. He replied “ If

you drink now you will be an alcoholic before you leave, if you don’t drink, you

will. These words were very prophetic not only for me, but, for most of the

guys. I won’t say that we became hardcore alcoholics, just that we worked real

hard to get crocked as often as possible. My first assignment on board was to be

a Mess Cook for four months. I have to say that during the first four weeks of

this my submarine career almost came to an end.

For those that do not know about Fleet Snorkel submarines there

is only one passage and in the Crews Mess the galley sink is located on the

starboard side. Needless to say when a guy is hard at work washing dishes his

back is facing the passage way. Being a “young and tender” new ETSN on board I

was subjected to some rather rude remarks of a sexual nature. This in and of

itself was pretty disconcerting to me because I was just 19 at the time and was

fairly straight laced and religious. As it happened things only got worse as the

first two weeks or so went by. It seemed that about half the crew was hell bent

on driving be crazy. As the guys would go past me while I was working at the

sink about half would either pat me on the butt, a few would grab me and dry

hump my backside, some would either tongue kiss my ears or put a hickey on my

neck. Bear in mind I could do little to fight these actions off because of what

I was doing a that I was pretty sure it was just a test to see how much I could

take, I wasn’t too sure about the second reason. At any rate after about two and

a half weeks I had had it. I had hickeys on both sides of my neck, (none

inflicted by a girl), and I probably had the cleanest ears on Oahu. I went to

see the COB and expressed my desire to disqualify myself from submarine duty

because it seemed that at least half the crew was queer. The COB must have had

some pretty good laughs at my expense over my complaint. The good new was that

the harassment stopped virtually immediately. By the time I came on duty next

day no one touched me. A few that bumped into me as they went by actually said

“excuse me” in a nice way. What a relief! The long and short of it was that my

second guess as to why was the correct one, I was being tested, unofficially, to

see if I could hack it.

Somewhere in late Nov 59, we moved to the shipyard and completed

the off load of the boat. The crew moved on board a Living Barge for the

duration of the shipyard availability. I remained on Mess Cooking duty until

near the end of the yard period when I was promoted to ET3 as a result of fleet

wide testing in Jan 60 and.

The overhaul included refurbishment of all major systems and

equipment onboard for each department including the electronics suite consisting

of a DAS-4 Loran navigation receiver, an AN/BPQ-1 (XN-1) Regulus guidance radar

system, a SS-2A Surface Search radar, an AN/BLR-1 and AN/WLR-3 Electronic

Countermeasures Receiving (ECM) set, an AN/UPS-1 IFF (Identification, Friend or

Foe), Transponder set and various audio recording and amplifying devices. The

ECM set included a separate retractable mast with directional antennas for

frequencies from 1 gigahertz to 12 gigahertz.

The shipyard availability also included renovation of the crew

berthing areas. This upgrade primarily consisted of new paint, new vinyl

asbestos floor covering and bunk lockers to replace the canvas bottomed bunks

installed originally.

There were some interesting events at the shipyard, the boat was

put in dry-dock revealing the entire boat, very impressive, another was firing

dummy hollow torpedoes into Pearl Harbor using only compressed air. Those dummy

fish would go more than a quarter mile trailing a wake of air bubbles, neat!

Cusk completed overhaul in Mar 1960 and performed shakedown

exercises including torpedo and Regulus missile guidance training off the coasts

of the Hawaiian Islands.

In May of 60 Cusk prepared and departed for a six

month WestPac cruise including outfitting the ship for NSA Electronic

Intelligence (ELINT) missions while deployed. Equipage for the ELINT missions

included installing additional HF receivers in the radio shack and changing out

the observation periscope to a NSA/Kolmorgan periscope equipped with a small

probe type antenna at the top of the periscope which was connected to a then

state of the art wide band receiver AN/ALR-1 additional equipment included a

AN/SLA-2 Pulse Analyzer, a frequency spectrum analyzer and a AN/SRD-7 Direction

finding receiver. The combination of the installed and temporary equipments

provided intercept and directional capabilities from 2-32 megahertz and from 500

megahertz thru 12 gigahertz frequencies. The SLA-2 provided a means of measuring

intercepted pulse width and pulse repetition rate. The WLR and ALR provided

quick intercept and directional abilities for known threat signals. The HF

receivers provided additional means of monitoring and intercepting voice and

code messages of Soviet transmissions for the NSA personnel (i.e.., Spooks).

It was during this period that my life’s attitude was

changed forever. I was doing my assigned tasks for the day cleaning behind the

equipment in the Missile Guidance room. ET2 Bill ‘Hog’ Jones the Leading ET and

LTJG Kreitzberg our division officer came down the ladder and started a

discussion about the new ET’s, meaning me and Dick Specht. They were unaware

that I was in hearing range. ENS Kreitzberg asked Jones what he thought of “that

Hrbacek kid”. Jones responded with something to the effect that ‘Hrbacek would

probably never amount to much, probably would never make second class’.

Needless to say I was very quiet during this discussion as I listened in on what

was being said about me. I took the comments to heart and started changing the

way I did and thought about things. It took a while, but, by the time I retired

I was senior to every enlisted guy I ever worked for. I have a great sense of

pride on this subject and I feel I owe it to ET2 Jones. By the time I left Cusk

I was LPO and was respected as a technician and work organizer both on and off

the boat.

Cusk arrived in mid June of 1960 in Yokosuka, Japan

and commenced load out for a mission. Briefings for the mission were conducted

for the Officers and electronics division personnel at Kamasea. This briefing

primarily spelled out what our mission objectives were to be and what ELINT,

(electronic intelligence), signals to look for. Signals of interest were to be

submarine type radars (Snoop Plate), any fire control type radars and a variety

of shore based surface and long range air search radars. Our mission was to

collect signal data for a master database of intercepted signals with

triangulated locations and or hull numbers for shipboard emitters. Additionally

we were to search for communications which might reveal Soviet surface and

submarine operations plans and procedures/tactics. We were to remain radio

silent on all bands and remain undetected if at all possible.

Off duty in Yokosuka was party time, cheap booze and

plenty of opportunities with the ladies. The Starlight and White Hat clubs were

favorite hang outs for Cusk crewmembers. Although I had drank myself to an

unconscious stupor before I had no Idea that it could be so pervasive amongst a

group of people. The common topic almost every day in the crews mess was ‘I’ll

never do that again’. Needless to say there were lots of hangovers on a daily

basis. Drinking and carousing around was the order of the day. Duty days were a

blessing in disguise, they allowed for a day of recovery.